Pony Express

The Pony Express was a fast mail service crossing the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, from April 1860 to October 1861. It became the west's most direct means of east-west communication before the telegraph and was vital for tying California closely with the Union just before the American Civil War.

The Pony Express was a mail delivery system of the Leavenworth & Pike's Peak Express Company of 1849 which in 1850 became the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company. This firm was founded by William H. Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B. Waddell.[1]

Built in 1858 as a luxury hotel, Patee House when it opened that year was one of the finest hotels west of the Mississippi. It served as the Pony Express headquarters from 1860 to 1861. It is one block away from the home of infamous outlaw Jesse James, where he was shot and killed by Robert Ford. After his murder, Jesse James' family took up lodging at this hotel and were interviewed by newspapermen of the time during their stay there.[2]

This original fast mail 'Pony Express' service had messages carried by horseback riders in relays to stations across the prairies, plains, deserts, and mountains of the Western United States. For its 18 months of operation, it briefly reduced the time for messages to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific coasts to about ten days, with telegraphic communication covering about half the distance across the continent and mounted couriers the rest.[3]

Founders of the Pony Express

William Russell, Alexander Majors and William Waddell, the three founders of the Pony Express, were already in the freighting business with more than 4,000 men, 3,500 wagons and some 40,000 oxen in 1858. They held government contracts for delivering army supplies to the West frontier, and Russell had a similar idea for contracts with the US Government for fast mail delivery.

By having a short route and using mounted riders rather than traditional stagecoaches, their proposal was to establish a fast mail service between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California with letters delivered in 10 days, a duration many said was impossible. It was not exactly overnight, but perhaps overpriced for the time, at $5 a half-ounce. The founders of the Pony Express hoped to win an exclusive government mail contract, something that did not come about.

Russell, Majors and Waddell organized and put together the Pony Express in just two months in the winter of 1860. It was an undertaking of enormous proportions, with 120 riders, 184 stations, 400 horses and several hundred of personnel, all during January and February 1860.[4]

Alexander Majors was a religious man and resolved "by the help of God" to overcome all difficulties. He presented each rider with a Bible and required this oath:

While I am the employ of A. Majors, I agree not use profane language, not to get drunk, not to gamble, not to treat animals cruelly and not to do anything else that is incompatible with the conduct of a gentleman. And I agree, if I violate any of the above conditions, to accept my discharge without any pay for my services.

– Oath sworn by Pony Express Riders

Pony Express demonstrated that a unified transcontinental system could be built and operated continuously year round. Since its replacement by the telegraph, the Pony Express has become part of the lore of the American West. Its reliance on the ability and endurance of individual riders and horses over technological innovation was part of the American rugged individualism of the Frontier times.

From 1866 until 1890, the Pony Express logo was used by Wells Fargo, which provided secure mail and freight services. The United States Postal Service (USPS) used "Pony Express" as a trademark for postal services in the US.[5] Freight Link international courier services, based in Russia, adopted the Pony Express trademark and a logo similar to that of the USPS [6].

Operation

A total of about 157 Pony Express stations were placed at intervals of about 10 miles (16 km) along the approximately 2,000 miles (3,200 km) route.[8] This was roughly the maximum distance a horse could travel quickly, either at a trot, a canter or a gallop, depending on the need. The rider changed to a fresh horse at each station, taking only the mail pouch called a mochila (from the Spanish for pouch or backpack) with him. The employers stressed the importance of the pouch. They often said that, if it came to be, the horse and rider should perish before the mochila did. The mochila was thrown over the saddle and held in place by the weight of the rider sitting on it. Each corner had a cantina, or pocket. Bundles of mail were placed in these cantinas, which were padlocked for safety. The mochila could hold 20 pounds (10 kg) of mail along with the 20 pounds of material carried on the horse. Included in that 20 pounds were a water sack, a Bible, a horn for alerting the relay station master to prepare the next horse, a revolver, and a choice of a rifle or another revolver. Eventually, everything except one revolver and a water sack was removed, allowing for a total of 165 pounds (75 kg) on the horse's back. Riders, who could not weigh over 125 pounds, changed about every 75–100 miles (120–160 km), and rode day and night. In emergencies, a given rider might ride two stages back to back, over 20 hours on a quickly moving horse.

It is unknown if riders tried crossing the Sierra Nevada in winter, but they certainly crossed central Nevada. By 1860 there was a telegraph station in Carson City, Nevada. The riders received $25 per week as pay. A comparable wage for unskilled labor at the time was about $1 per week.

Alexander Majors, one of the founders of the Pony Express, had acquired more than 400 horses for the project. These averaged about 14½ hands (1.47 m) high and averaged 900 pounds (410 kg)[9] each; thus, the name pony was appropriate, even if not strictly correct in all cases.

Pony Express Stations

Along the route used by the Pony Express there were 184 stations. The route was divided up into five Divisions:[10] To maintain the rigid schedule, 157 relay stations were located from 5 to 20 miles apart. At each Swing Station riders would exchange their tired mounts for fresh ones, while Home Stations housed the riders between runs. This technique allowed the mail to be whisked across the continent in record time. Each rider rode about 75 miles per day.[11]

Division One: Stations between St. Joseph and Fort Kearney [12]

Division Two: Stations between Fort Kearney and Horseshoe Creek [13]

Division Three: Stations between Horseshoe Creek and Salt Lake City [14]

Division Four: Stations between Salt Lake City and Robert's Creek [15]

Division Five: Stations between Roberts Creek and Sacramento [16]

Route of the Pony Express

The roughly 1900 mile route[17] roughly followed the Oregon Trail, and California Trail to Fort Bridger in Wyoming and then the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. From there it roughly followed the Central Nevada Route to Carson City, Nevada before passing over the Sierras into Sacramento, California.

|

The route started at St. Joseph, Missouri on the Missouri River, it then followed what is modern day US 36—the Pony Express Highway—to Marysville, Kansas, where it turned northwest following Little Blue River to Fort Kearny in Nebraska. Through Nebraska it followed the Great Platte River Road, cutting through Gothenburg, Nebraska and passing Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff, clipping the edge of Colorado at Julesburg, Colorado, before arriving at Fort Laramie in Wyoming. From there it followed the Sweetwater River, passing Independence Rock, Devil's Gate, and Split Rock, to Fort Caspar, through South Pass to Fort Bridger and then down to Salt Lake City. From Salt Lake City it generally followed the Central Nevada Route blazed by Captain James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1859. This route roughly follows today's U.S. Highway 50 across Nevada and Utah. It crossed the Great Basin, the Utah-Nevada Desert, and the Sierra Nevada near Lake Tahoe before arriving in Sacramento. Mail was then sent via steamer down the Sacramento River to San Francisco. On a few instances when the steamer was missed, riders took the mail via horseback to Oakland, California.

First journeys

Westbound

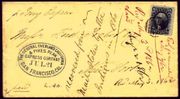

The first Westbound Pony Express trip left St. Joseph on April 3, 1860 and arrived ten days later in San Francisco, California on April 14. These letters were sent under cover from the East to St. Joseph, and never directly entered the U.S. mail system. To this day there is only a single letter known to exist from the inaugural westbound trip from St. Joseph, Missouri to San Francisco, California.[18] The mailing depicted below is on a pre-stamped (embossed) envelope, first issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1855, used five years later here.[19]

The messenger delivering the mochila from New York and Washington missed a connection in Detroit and arrived in Hannibal, Missouri, two hours late. The railroad cleared the track and dispatched a special locomotive called the "Missouri" with a one-car train to make the 206-mile (332 km) trek across the state in a record 4 hours, 51 minutes — an average of 40 miles per hour (64 km/h).[20] It arrived at Olive and 8th Street — a few blocks from the company's new headquarters in a hotel at Patee House at 12th Street and Pennsylvania and the company's nearby stables on Pennsylvania. The first pouch contained 49 letters, five private telegrams, and some papers for San Francisco and intermediate points.[21]

St. Joseph Mayor M. Jeff Thompson, William H. Russell and Alexander Majors gave speeches before the mochila was handed off. The ride began at about 7:15 p.m. The St. Joseph Gazette was the only newspaper included in the bag.

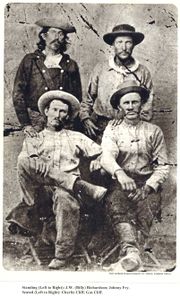

The identity of the first rider has long been in dispute. The St. Joseph Weekly West (April 4, 1860) reported Johnson William Richardson was the first rider. [22] Johnny Fry is credited in some sources as the rider. Nonetheless, the first westbound rider carried the pouch across the Missouri River ferry to Elwood, Kansas. The first horse-ridden leg of the Express was only about a half mile (800 m) from the Express stables/railroad area to the Missouri River ferry at the foot of Jules Street. Reports indicated that horse and rider crossed the river. In later rides, the courier crossed the river without a horse and picked up his mount at a stable on the other side.

The first westbound mochila reached its destination, San Francisco, on April 14, at 1:00 a.m. [23]

|

|

Eastbound

The first eastbound Pony Express trip left San Francisco, California, on April 3, 1860 and arrived at its destination some ten days later in St. Joseph, Missouri. From St. Joseph, letters were placed in the U.S. mails for delivery to eastern destinations. There are only two letters known to exist from the inaugural eastbound trip from San Francisco to St. Joseph.[24]

|

|

Pony Express Mail

As the Pony Express Mail service existed briefly in 1860 and 1861 there are consequently very few examples of surviving Pony Express mail today. Also contributing to the scarcity of surviving Pony Express mail was the fact that the cost to send a 1/2 ounce letter was $5.00 at the beginning, a costly sum in those days and mostly unaffordable to the general public. By the end period of the Pony Express, the price had dropped to $1.00 per 1/2 ounce. Even the $1.00 rate was considered a lot of money (about $85) just to mail one letter in those days. As this mail service was also a frontier enterprise, removed from the general population back east, along with the largely unaffordable rates, there are consequently few pieces of surviving Pony Express mail in the hands of collectors and museums today. Presently there are only 250 known examples of Pony Express mail.[18]

Postmarks

Fastest with the News

In 1860 senior partner of 'Russell, Majors, and Waddell.', William Russell, one of the biggest investors in the Pony Express, used the 1860 presidential election as a way to promote the Pony Express and how fast it could deliver the U.S. Mail. Assuring that there would be fresh riders and horses along the entire Pony Express route, Russell, prior to the election, hired extra riders and ensured that fresh relay horses were available along the route. On November 7, 1860, a Pony Express rider departed Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory (the eastern end of the telegraph line) with the election results. Riders sped along the route, over snow-covered trails and into Fort Churchill, Nevada Territory (the western end of the telegraph line). California’s newspapers received word of Lincoln’s election only seven days and 17 hours after the East Coast papers, an unrivaled feat at the time.[26]

Indian attacks on Pony Express

The Paiute War was a minor series of raids and ambushes initiated by the Paiute Indian tribe in Nevada and which resulted in the disruption of mail services of the Pony Express. It took place from May through June 1860, though sporadic violence continued for a period afterward. In the brief history that the Pony Express operated only once did the mail not go through. After completing eight weekly trips from both Sacramento and Saint Joseph, the Pony Express was forced to suspend mail services because of the outbreak of the Paiute Indian War in May 1860.

Approximately 6,000 Paiutes in Nevada had suffered during a winter of fierce blizzards that year. By spring, the whole tribe was ready to embark on a war, except for the Paiute chief named Numaga. For three days Numaga fasted and argued for peace. However, on May 7 a few Indians raided the Williams Pony Express Station anyway, killing five men.

During the following weeks, other isolated incidents occurred when whites in Paiute country were ambushed and killed. The Pony Express was a special target. Seven other express stations were also attacked; some 16 employees were killed and approximately 150 express horses were either stolen or driven off. The Paiute war cost the Pony Express company about $75,000 in livestock and station equipment, not to mention the loss of life. In June of that year, the Paiute uprising had been ended through the intervention of U.S. government troops, after which four delayed mail shipments from the East were finally brought to San Francisco on June 25, 1860.[28][11]

During this brief war, one Pony Express mailing, which left San Francisco on July 21, 1860 did not immediately reach its destination; the mail pouch (Mochila) did not arrive in St. Joseph and then on to New York until almost two years later.

Famous riders

Back in 1860, riding for the Pony Express was difficult work – riders had to be tough and lightweight. There is a famous advertisement that reportedly read, "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred." [29]

The Pony Express had an estimated 80 riders that were in use at any one given time. In addition, there were also about 400 other employees including station keepers, stock tenders and route superintendents. Many young men applied for jobs with the Pony Express, all eager to face the dangers and the challenges that sometimes lay along the delivery route. Famous American author Mark Twain, who saw the Pony Express in action first hand, described the riders as: "... usually a little bit of a man". Though the riders were small, lightweight, generally teenage boys, their untarnished record proved them to be heros of the American West for the much needed and dangerous service they provided for the nation.[11]

A list of riders has been compiled by the staff of the St. Joseph Museum from various sources, including accounts from people who knew riders, relatives of riders and newspapers. Some of the riders' names are listed in reference.[30][11]

First riders

The first westbound rider to depart St. Joseph has been disputed but at this late date most historians have boiled it down to either Johnny Fry or Billy Richardson [31] [22] [32][33] also known as Johnson William Richardson. Both Expressmen were hired at St. Joseph for A. E. Lewis' Division which ran from St. Joseph to Seneca, Kansas, a distance of eighty miles. They covered at an average speed of twelve and a half miles per hour, including all stops.[34] Before the mail pouch was delivered to the first rider, time was taken out for ceremonies and several speeches. First, Mayor M. Jeff Thompson gave a brief speech on the significance of the event for St. Joseph. Then William H. Russell and Alexander Majors addressed the gala crowd about how the Pony Express was just a "precursor" to the construction of a transcontinental railroad. At the conclusion of all the speeches, approximately 7:15 p.m., Russell turned the mail pouch over to the first rider. A cannon fired, the large assembled crowd cheered, and the rider dashed to the landing at the "foot of Jules Street where the ferry boat Denver, alerted by the signal cannon, waited to carry the horse and rider across the Missouri River to Elwood, Kansas Territory.[11] On April 9 at 6:45 p.m., the first rider from the east reached Salt Lake City, Utah. Then, on April 12, the mail pouch reached Carson City, Nevada at 2:30 p.m. The riders raced over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, through Placerville, California and on to Sacramento. Around midnight on April 14, 1860, the first mail pouch was delivered via the Pony Express to San Francisco.[35]

James Randall is credited as the first eastbound rider from the San Francisco Alta telegraph office since he was on the steamship Antelope to go to Sacramento.[36] Mail for the Pony Express left San Francisco at 4:00 pm, carried by horse and rider to the waterfront, and then on by steamboat to Sacramento where it was picked up by the Pony Express rider. At 2:45 a.m., William (Sam) Hamilton was the first Pony Express rider to begin the journey from Sacramento. He rode all the way to Sportsman Hall Station where he gave his mochila filled with mail to Warren Upson.[37] A California Registered Historical Landmark's plaque at the site reads:

This was the site of Sportsman's Hall, also known as the Twelve-Mile House. The hotel operated in the late 1850's and 1860's by John and James Blair. A stopping place for stages and teams of the Comstock, it became a relay station of the central overland Pony Express. Here, at 7:40 a.m., April 4, 1860, Pony rider William (Sam) Hamilton, riding in from Placerville, handed the Express mail to Warren Upson who, two minutes later, sped on his way eastward.

– Plaque at Sportsman Hall

William Cody

Probably more than any other rider in the Pony Express, William Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill epitomizes the legend and the folk lore of the Pony Express. Numerous stories have been told of young Cody's adventures as a Pony Express rider. When Cody was only 15 years old he was employed as a rider and was given a short 45-mile delivery run from the township of Julesburg which lay to the west. After some months he was transferred to Slade's Division in Wyoming where he made the longest non-stop ride from Red Buttes Station to Rocky Ridge Station and back when he found that his relief rider had been killed. The distance of 322 miles over one of the most dangerous sections of the entire trail was completed in 21 hours and 40 minutes. It took a total of 21 horses to complete this run.[11] Cody was present for every significant chapter in young western history, including the gold rush, the building of the railroads, and cattle herding on the Great Plains—and found himself playing a part in nearly every one of these crucial stages of development. A career as a scout during the Civil War earned him his nickname and established his notoriety as a model frontiersman.[38]

Robert Haslam

"Pony Bob" Haslam was among the most brave, resourceful, and best known riders of the Pony Express. He was born January 1840 in London, England, and came to U.S. as a teen. Haslam was hired by Bolivar Roberts, helped build the stations, and was given the mail run from Friday's Station at Lake Tahoe to Buckland’s Station near Fort Churchill which was 75 miles to the east. Perhaps his greatest ride, 120 miles in 8 hours and 20 minutes while wounded, was an important contribution to the fastest trip ever made by the Pony Express. The message carried Lincoln's inaugural address. Pony Bob Haslam's ride was the result of the Indian problems in 1860. He had received the eastbound mail (probably the May 10 mail from San Francisco) at Friday's Station. At Buckland's Station his relief rider was so badly frightened over the Indian threat that he refused to take the mail. Haslam agreed to take the mail all the way to Smith's Creek for a total distance of 190 miles without a rest. After a rest of nine hours, he retraced his route with the westbound mail. At Cold Springs he found that Indians had raided the place, killing the station keeper and running off all of the stock. Finally he reached Buckland's Station, making the 380-mile round trip the longest on record.[11] On the ride he was shot through the jaw with an Indian arrow, losing three teeth.[39]

Jack Keetley

Jack Keetley was hired by A. E. Lewis for his Division at the age of nineteen, and put on the run from Marysville to Big Sandy. He was one of those who rode for the Pony Express during the entire nineteen months of its existence.

Jack Keetley's longest ride, upon which he doubled back for another rider, ended at Seneca where he was taken from the saddle sound asleep. He had ridden 340 miles in thirty-one hours without stopping to rest or eat.[11][40] After the Pony Express was disbanded, Keetley went to Salt Lake City where he engaged in mining.[41]

In 1907, Keetley wrote the following letter (excerpt):

Salt Lake City, Utah, August 21, 1907

Mr. Houston Wyeth, St. Joseph, MO.

Dear Sir: -- Yours of the 17th inst. received, and in reply will say that Alex Carlyle was the first man to ride the Pony Express out of St. Joe. He was a nephew of the superintendent of the stage line to Denver, called the "Pike's Peak Express." The superintendent's name was Ben Fickland. Carlyle was a consumptive, and could not stand the hardships, and retired after about two months trial, and died within about six months after retiring. John Frye was the second rider, and I was the third, and Gus Cliff was the fourth. I made the longest ride without a stop, only to change horses. It was said to be 300 miles and was done a few minutes inside of twenty-four hours. I do not vouch for the distance being correct, as I only have it from the division superintendent, A.E. Lewis, who said that the distance given was taken by his English roadometer which was attached to the front wheel of his buggy which he used to travel over his division with, and which was from St. Joe to Fort Kearney.[40] . . .

– Jack Kettley

Horses

An estimated 400 horses in total were used by the Pony Express to deliver the mail. Horses were selected for swiftness and endurance. On the east end of Pony Express route the horses were usually selected from US Calvary units. At the west end of the pony Express route in California, W.W. Finney purchased 100 head of short coupled stock called "California Horses"' while A.B. Miller purchased another 200 native ponies in and around the Great Salt Lake Valley. The horses were ridden at a quickly between stations, an average of 15 miles, and then were relieved and a fresh horse would be exchanged for the one that just arrived from its strenuous run.

During his route of 80 to 100 miles, a Pony Express rider would change horses 8 to 10 times. The horses were ridden at a fast trot, canter or gallop, around 10 to 15 miles per hour and at times they were driven to full gallop at speeds up to 25 miles per hour. Horses of the Pony Express were purchased in Missouri, Iowa, California, and some western U.S. territories.

The various types of horses ridden by riders of the Pony Express included Morgans and thoroughbreds which were often used on the eastern end of the trail. Pintos were often used in the middle section and mustangs were often used on the western (more rugged) end of the mail route. [42]

Saddle

In 1844 years before the Pony Express came to St. Joseph, Israel Landis opened a small saddle and harness shop there. His business expanded as the town grew, and when the Pony Express came to town Landis was the ideal candidate to produce saddles for the new found Pony Express. Because Pony Express riders rode their horses at quickly over a distance of ten and more miles between stations, every consideration was made to reduce the overall weight the horse had to carry. To help reduce this load, special light weight saddles were designed and crafted. Using less leather and fewer metallic and wood components they fashioned a saddle that was similar in design to the regular stock saddle generally in use in the West at that time. [43]

The mail pouch was a separate component to the saddle that made the Pony Express unique. Standard mail pouches for horses were never employed because of their size and shape, as it would be time consuming to attach to the saddle, and would cause undue delay in changing mounts. To get around this difficulty, a mochila, or covering of leather, was thrown over the saddle. The saddle horn and cantle projected through holes which were cut in the mochila. Attached to the broad leather skirt of the mochila were four cantinas, or boxes of hard leather.[43]

Closing

Although the Pony Express proved that the central/northern mail route was viable, Russell, Majors and Waddell did not get the contract to deliver mail over the route. The contract was instead awarded to Jeremy Dehut in March 1861, who had taken over the southern Congressionally favored Butterfield Overland Mail Stage Line. Holladay took over the Russell, Majors and Waddell stations for his stagecoaches.

Shortly after the contract was awarded, the start of the American Civil War caused the stage line to cease operation. From March 1861, the Pony Express ran mail only between Salt Lake City and Sacramento. The Pony Express announced its closure on October 26, 1861, two days after the transcontinental telegraph reached Salt Lake City and connected Omaha, Nebraska and Sacramento, California.[44] Other telegraph lines connected points along the line and other cities on the east and west coasts.

The Pony Express had grossed $90,000 and lost $200,000.[45] In 1866, after the American Civil War was over, Holladay sold the Pony Express assets along with the remnants of the Butterfield Stage to Wells Fargo for $1.5 million.

Commemoration

In 1869 the US Post Office issued the first US Postage stamp to depict an actual historic event, and the subject that was chosen was the Pony Express. Up until this time only the faces of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson were found on the face of US Postage.[46] Sometimes mistaken for an actual stamp used by the Pony Express, the 'Pony Express Stamp' issue was released in 1869 (8 years after the Pony Express service had ended) to honor the men who rode the long and sometimes dangerous journeys and to commemorate the service they provided for the nation.

National Pony Express Association (NPEA) is a non-profit, volunteer-led historical organization. Its purpose is to preserve the original Pony Express trail and to continue the memory and importance of Pony Express in American history in partnership with the National Park Service, Pony Express Trail Association, and the Oregon-California Trails Association.

April 1, 2010 was the Pony Express' 150th anniversary. Located in St. Joseph, Missouri, the Patee House Museum, which was the Pony Express' headquarters, hosted events celebrating the anniversary.[47]

Pony Express historical research

The foundation of accountable Pony Express history rests in the few tangible areas where records, papers, letters and mailings have yielded the most historical evidence. Up until the 1950s most of what was known about the short lived Pony Express was the product of a few accounts, hearsay and folk Lore, generally true in their overall aspects, but lacking in verification in many areas for those who wanted to explore the history surrounding the founders, the various riders and station keepers or who were interested in stations or Forts along the Pony Express route itself.

The most complete books on the Pony Express are The Story of the Pony Express and Saddles and Spurs by Raymond & Mary Settle and Roy Bloss. Settle's account is unique as he was the first writer and historical researcher to make use of the William B. Waddell's papers, now a collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California. (Waddell was one of the founders of the Pony Express) Mr. Settle wrote in the middle 1950's. Mr. Bloss was a writer for the Pony Express Centennial. While Settle's work was published generally without his annotations and notes the writer's background here is unique and Settle does have an excellent bibliography. When Settle prepared to publish his well researched account he indeed had a good volume of footnotes, citations all prepared, but the editors chose not to use most of them. Instead they opted for a less expensive approach to print and publish and released an accurate but more simplified account. Settle was not pleased with this new and sudden development as he put much time and effort into the annotations. Yet the account Settle wrote was and is a definitive one and is considered the best account on the history of the Pony Express amongst many historians. [11][48]

Legacy

Wells Fargo used the Pony Express logo for its guard and armored car service. The logo continued to be used when other companies took over the security business into the 1990s. Effective 2001, the Pony Express logo was no longer used for security businesses since the business has been sold.[49]

In June 2006, the United States Postal Service announced it had trademarked "Pony Express" along with Air Mail.[50]

"Pony Express" is a trademarked name used by Freight Link international courier services company in Russia; their logo is similar to the one trademarked by United States Postal Service with "Since 1860" written under the image.[51]

Its route has been designated the Pony Express National Historic Trail. Approximately 120 historic sites along the trail may eventually be open to the public, including 50 stations or station ruins.[52]

Pony Express memorial statues are in Sacramento; Stateline, Nevada; Reno, Nevada; Salt Lake City; Casper, Wyoming; Julesburg, Colorado; Marysville, Kansas; North Kansas City, Missouri; Sidney, Nebraska and St. Joseph. The original and most famous is the one dedicated on April 20, 1940, in St. Joseph. It was sculpted by Hermon Atkins MacNeil. It is at City Hall Park. The city has rejected proposals to move it to the park opposite the stables.

The Sidney, Nebraska monument, dubbed "The National Pony Express Monument," commemorates all eight states with a granite marker each, and state flags. Three head stones depict the founders, the trail and the National Pony Express Association. Two benches commemorate the rider oath and the creator of the mochilla.

Eagle Mountain, Utah, located on the original Pony Express Trail in Utah, has several locations and events that commemorate the Pony Express.

- Pony Express Boulevard in Eagle Mountain, Utah may be the only street built on the original Pony Express Trail that is named after the Pony Express.

- Pony Express Days, the annual community celebration of Eagle Mountain, are celebrated the first week of June of each year.

- The Alpine School District's Pony Express Elementary School is located in Eagle Mountain and is a K-5 elementary school.

- Eagle Mountain also has an official Pony Express monument on the site of the original Joe's Dug Out station on the Pony Express Trail.

- Neighborhoods in Eagle Mountain are named after stations on the Pony Express Trail, such as: "Cold Spring", "Kennekuk", "Ash Point", and "Kiowa". A major road is named "Sweetwater", after another station, and a charter High School is named "Rockwell."

- The term "pony express" has come to be used as a type of genericized trademark for other similar mail routes.

In popular culture

The continued remembrance and popularity of the Pony Express can be linked to Buffalo Bill Cody, his autobiographies, and his Wild West Show. The first book dedicated solely to the Pony Express was not published until 1900.[53] However, in his first autobiography, published in 1879, Cody claims to have been an Express rider.[54][55] While this claim has recently come under dispute[56], his show became the "primary keeper of the pony legend" when it premiered as a scene in the Wild West Show.[57]

Film

- The Pony Express - (1925) - A silent film epic directed by James Cruze. Starring Ricardo Cortez, Betty Compson, Ernest Torrence, Wallace Beery, and George Bancroft.[58]

- Frontier Pony Express - (1939) - A film directed by Joseph Kane. Starring Roy Rogers and Mary Kane.[59]

- Pony Post - (1940) - A 'B' western directed by Ray Taylor. Starring Johnny Mack Brown, Nell O'Day, Fuzzy Knight,and Iron Eyes Cody.[60]

- Plainsman and the Lady - (1946) - Film centered on the beginnings of the Pony Express. Directed by Joseph Kane. Starring William Elliott, Vera Ralston, and Donald Barry.[61]

- Pony Express - (1953) - "GALLOPING THRILLS! A mighty adventure when America's destiny rode in the saddle bags of the...PONY EXPRESS." Pairs Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok in the establishment of the Pony Express. - Directed by Jerry Hopper. Starring Charlton Heston, Rhonda Fleming, and Forest Tucker.[62]

- Last of the Pony Riders - (1953) - Directed by George Archainbaud. Starring: Gene Autry, Smiley Burnette,and Kathleen Case.[63]

- The Pony Express Rider - (1976) - The Pony Express is used as means of revenge. Directed by Robert Totten. Starring: Stewart Petersen, Jack Elam, Joan Caulfield, Slim Pickens, and Dub Taylor.[64]

Television

- The Range Rider - (1951–1953) - The Pony Express was featured in season 1 in an episode titled, "The Last of the Pony Express."[65]

- Pony Express - (1959–1960) - Little known television series centered on the Express.[66]

- Bonanza - (1959–1973) - The Pony Express was featured in season 7 during a two-part episode titled, "Ride the Wind."[67]

- The Young Riders, a western television series created by Ed Spielman that presents a fictionalized account of a group of young Pony Express riders based at the Sweetwater Station in the Nebraska Territory during the years leading up to the American Civil War. The show ran on ABC from September 20. 1989 to July 23, 1992.

- The Pony Express is depicted in Spielberg's mini-series "Into the West" (2005).

Other

- McGraw Hill and Amerikids USA produced the game Pony Express Rider in 1996. In the game the Pony Express helps the Union outwit Confederate spies who want California to secede[68]

- A school in Utah is named Pony Express Elementary. Its said the school was built around the area where pony express rider rode through.

- The Pony Express (roller coaster) is a steel motorbike roller coaster currently open at Knott's Berry Farm in Buena Park, California. It features sweeping turns and sudden drops.

Gallery

Russell, Majors, Waddell, founders of the Pony Express |

William H. Russell |

William B. Waddell |

William Fisher, Pony Express rider |

U.S. Postal Service trademarked Pony Express logo[5] |

Coming and Going of the Pony Express. Painting by Frederic Remington, 1900 |

Parade celebrating Pony Express Days in Eagle Mountain, Utah. |

Wells Fargo security patch depicting Pony Express rider logo |

See also

- Postage stamps and postal history of the United States

- Postal History

- Philately

- Pony Express Museum

- Joseph Alfred Slade

- Yam (route)

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Philately

References

- ↑ NPS.gov, National Park Service, accessed 29 Oct 2009

- ↑ Pony Express National Museum: http://www.ponyexpressjessejames.com/index.php

- ↑ Bradley, Glenn D. The Story of the Pony Express: An Account of the Most Remarkable Mail Service Ever in Existence, and Its Place in History, Project Gutenberg Release #4671

- ↑ Pony Express National Museum: http://www.ci.st-joseph.mo.us/history/ponyexpress.cfm

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 United States Patent and Trademark Office S/N 75218057 et al

- ↑ Freight Link Russia: http://www.ponyexpress.ru/index-en.php

- ↑ NPS.gov

- ↑ St. Joseph Pony Express Museum accessed 27 Jan 2009

- ↑ Pony Express horses

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service:Pony Express Historic Resource Study, 1994, Anthony Godfrey, Ph.D.: http://www.nps.gov/archive/poex/hrs/hrs4b.htm

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Raymond W. and Mary Lund Settle, Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1955), 199.

- ↑ Division One: Stations between *St. Joseph and Fort Kearney Missouri: 1. St. Joseph Station Area Kansas: 2. Troy Station 3. Lewis Station 4. Kennekuk (Kinnekuk) Station 5. Kickapoo/Goteschall Station 6. Log Chain Station 7. Seneca Station 8. Ash Point/Laramie Creek Station 9. Guittard (Gantard's, Guttard) Station 10. Marysville Station 11. Cottonwood/Hollenberg Station 12. Atchison Station 13. Lancaster Station Nebraska: 14. Rock House Station 15. Rock/Turkey Creek Station 16. Virginia City 17. Big Sandy Station 18. Millersville/Thompson's Station 19. Kiowa Station 20. Little Blue/Oak Grove Station 21. Liberty Farm Station 22. Spring Ranch/Lone Tree Station 23. Thirty-two Mile Creek Station 24. Sand Hill/Summit Station 25. Hook's/Kearney/Valley Station 26. Fort Kearney Summary

- ↑ Division Two: Stations between Ft. Kearney and Horseshoe Creek Nebraska (continued): 27. Seventeen Mile/Platte Station 28. Garden Station 29. Plum Creek Station 30. Willow Island/Willow Bend Station 31. Cold Water/Midway Ranch Station 32. Gilman's Station 33. Machette's Station (Gothenburg) 34. Cottonwood Springs Station 35. Cold Springs Station 36. Fremont Springs Station 37. O'Fallon's Bluff/Dansey's/Elkhorn Station 38. Alkali Lake Station 39. Gill's/Sand Hill Station 40. Diamond Springs Station 41. Beauvais Ranch Station Colorado: 42. Frontz's/South Platte Station 43. Julesburg Station Nebraska (continued): 44. Nine Mile Station 45. Pole Creek No. 2 Station 46. Pole Creek No. 3 Station 47. Midway Station 48. Mud Springs Station 49. Court House (Rock) Station 50. Chimney Rock Station 51. Ficklin's Springs Station 52. Scott's Bluff(s) Station 53. Horse Creek Station Wyoming: 54. Cold Springs/Spring Ranch/Torrington Station 55. Verdling's/Bordeaux/Bedeau's Ranch/Fort Benard Station 56. Fort Laramie Station 57. Nine Mile/Sand Point/Ward's/Central Star Station 58. Cottonwood Station 59. Horseshoe Creek/Horseshoe Station Summary

- ↑ Division Three: Stations between Horseshoe Creek and Salt Lake City Wyoming (continued): 60. Elk Horn Station 61. La Bonte Station 62. Bed Tick Station 63. Lapierelle/La Prele Station 64. Box Elder (Creek) Station 65. Deer Creek Station 66. Little Muddy Station 67. Bridger Station 68. Platte Bridge/North Platte Station 69. Red Butte (s) Station 70. Willow Springs Station 71. Horse/Greesewood Creek Station 72. Sweetwater Station 73. Devil's Gate Station 74. Plant's/Plante Station 75. Split Rock Station 76. Three Crossings Station 77. Ice Slough/Ice Springs Station 78. Warm Springs Station 79. Rocky Ridge/St. Mary's Station 80. Rock Creek Station 81. Upper Sweetwater/South Pass Station 82. Pacific Springs Station 83. Dry Sandy Station 84. Little Sandy Creek Station 85. Big Sandy Station 86. Big Timber Station 87. Green River (Crossing) Station 88. Michael Martin's Station 89. Ham's Fork Station 90. Church Butte(s) Station 91. Millersville Station 92. Fort Bridger 93. Muddy Creek Station 94. Quaking Asp/Aspen/Springs Station 95. Bear River Station Utah: 96. The Needles/Needle Rock(s) Station 97. (Head of) Echo Canyon Station 98. Halfway Station 99. Weber Station 100. Brimville Emergency Station 101. Carson House Station 102. East Canyon Station 103. Wheaton Springs Station 104. Mountain Dell/Dale Station 105. Salt Lake City Station

- ↑ Division Four: Stations between Salt Lake City and Robert's Creek Utah: (continued): 106. Trader's Rest/Traveler's Rest Station 107. Rockwell's Station 108. Dugout/Joe's Dugout Station 109. Camp Floyd/Fairfield Station 110. Pass/East Rush Valley Station 111. Rush Valley/Faust's Station 112. Point Lookout/Lookout Pass Station 113. Government Creek Station 114. Simpson's Springs/Egan's Springs Station 115. River Bed Station 116. Dugway Station 117. Black Rock Station 118. Fish Springs Station 119. Boyd's Station 120. Willow Springs Station 121. Willow Creek Station 122. Canyon/Burnt Station 123. Deep Creek Station Nevada: 124. Prairie Gate/Eight Mile Station 125. Antelope Springs Station 126. Spring Valley Station 127. Schell Creek Station 128. Egan's Canyon/Egan's Station 129. Bates'/Butte Station 130. Mountain Spring(s) Station 131. Ruby Valley Station 132. Jacob's Well Station 133. Diamond Springs Station 134. Sulphur Springs Station 135. Roberts Creek Station

- ↑ Division Five: Stations between Roberts Creek and Sacramento Nevada (continued): 136. Camp Station/Grub(b)s Well Station 137. Dry Creek Station 138. Simpson Park Station 139. Reese River/Jacob's Spring Station 140. Dry Wells Station 141. Smith's Creek Station 142. Castle Rock Station 143. Edward's Creek Station 144. Cold Springs/East Gate Station 145. Middle Gate Station 146. West Gate Station 147. Sand Springs Station 148. Sand Hill Station 149. Carson Sink/Sink of the Carson Station 150. Williams Station 151. Desert/Hooten Wells Station 152. Buckland's Station 153. Fort Churchill Station 154. Fairview Station 155. Mountain Well Station 156. Stillwater Station 157. Old River Station 158. Bisby's Station 159. Nevada Station 160. Ragtown Station 161. Desert Wells Station 162. Miller's/Reed's Station 163. Dayton Station 164. Carson City Station 165. Genoa Station 166. Friday's/Lakeside Station California: 167. Woodford's Station 168. Fountain Place Station 169. Yank's Station 170. Strawberry Station 171. Webster's/Sugar Loaf House Station 172. Moss/Moore/Riverton Station 173. Sportsman's Hall Station 174. Placerville Station 175. El Dorado/Nevada House/Mud Springs Station 176. Mormon Tavern/Sunrise House Station 177. Fifteen Mile House Station 178. Five Mile House Station 179. Pleasant Grove House Station 180. Duroc Station 181. Folsom Station 182. Sacramento Station 183. Benicia, Martinez, and Oakland Stations 184. San Francisco Station

- ↑ The Pony Express Trail

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 The Pony Express, A Postal History, 2005, by R. Frajola, G. Kramer and S. Walske: http://www.rfrajola.com/books.htm

- ↑ Scotts Specialized catalogue of U.S. Postage Stamps / Envelopes

- ↑ Hannibal & Joseph Railroad at xphomestation.com

- ↑ The Great Race Against Time: Birth of the Pony Express - National Park Service

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kansas Historical Quarterly

- ↑ First Rider - Westbound at xhomestation.com

- ↑ The Pony Express, A Postal History, Published 2005 by the Philatelic Foundation: By R. Frajola, G. Kramer and S. Walske: http://www.rfrajola.com/books.htm

- ↑ Richard Frajola, Philatelist

- ↑ Smithsonian National Postal Museum / Pony Express

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps

- ↑ Sand in a Whirlwind: The Paiute Indian War 1860. University of Nevada Press, 1985.

- ↑ Poster claimed to be a hoax by one historian, Joseph Nardone, who failed in his effort to find it in newspaper archives. Nardone also fails to establish 'why' some one would create such a hoax, in 1902, the date he claims is the earliest possible date of the poster in question. Also, Nardone doesn't explain why a poster printed for a wall should always be expected to appear in newspapers.

- ↑ - List of Pony Express riders names taken from 'Saddles and Spurs', by Settle and Settle - * Thomas Anderson * Juan Santos Avila * Samuel Baker * James William Bearden * Stacy Bell * Charles H. ("Doc") Brink * Van Evrie Brown * William Bruce * George Henry Butterfield * Andrew Jaxson Case * Luther Conner * James Crowley * William J. Davis * Carl Wreathum Debitt * Berverly R. Dennis * John S.B. Dietz * William Dixon * Alexander Frazier Edward * Josiah Giberton EnglishNew 5/19/2007 * Abram Fredendall * Charles P. Frost * William Houston Fulkerson * Antonio Gonzales * Pedro Gonzales * William Gooding * Richard Francis Goward * Peter Nease Guymon * William Hazelwood * Patrick Hill * Billy (Will) Holt * Jimmy Hood * John Humphreys * Nelson Edward Jacobs * Will G. Johnson * Charles Burton Lambert * Michael LeGarde * Andrew Jackson Lucas * Azariah Lundy * David Martin * Marian Martin * George McGraw * George Monroe * Joe Nappier * Shorty Neal * Solomon K. Nellis * Thaddeus J. Posey * Bob Olinger * John Bruff Queen * Reinert Reime * W. T. Richardson * Erasmus Benjamin Riley * James R. Robertson * William Robinson * James Robinson * Issac Richard Ross * John Roth * Frank Russell * Hilario Saenz * Frederick Sander * Joel Scott * Martin Shull * Jack Souter * Levi Murphy (Merf) Southern * George H. Stevens * William Thomas Strange * Joseph R. Tagert * George Richardson Tylee * Walter Waugh * Frank Webner * William West * Samuel Paul Westberg * Dominique Winther * Cyrus Wirt * Charles Westley Wood * Loamma Worley * Austin Yokeley * Youngker * Andrew Ole Anderson * Thomas Bedford * James Bently * Asher Bigelow * Michael Casey * Josiah Faylor * James Bean [Benjamin] Hamilton * Lucius Lodosky Hickok * Thomas Landon * James Madison Lenhart * Joseph Malcom * John Mufsey * Edward Pollinger * Sewel Ridley * Edward Sterling * Littleton Tough * Thomas Thornhill Willson

- ↑ National Historic Trail - Pony Express Stables

- ↑ Pony Express Resource Study - Chapter 2

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ THE STORY OF THE PONY EXPRESS, 1913, by Glen Bradley, history professor at the University of Toledo.

- ↑ U.S. National Park Service

- ↑ The Pony Express by Jean Kinney Williams, Compass Point Books, page 27

- ↑ PONY EXPRESS Historic Resource Study, SPORTSMAN'S HALL STATION

- ↑ Joshua Johns The University of Virginia http://www.xphomestation.com/frm-history.html

- ↑ Wyoming Tales and Trails http://www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com/OregonTrail4.html

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Visscher, William Lightfoot. Pony Express, A Thrilling and Truthful History. Vistabooks, 1980. An authentic narrative with photographs of the Pony Express and the Old West.

- ↑ Settle, Raymond W. and Mary Lund Settle. Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga. University of Nevada Press, 1972.

- ↑ Stong, Phil. Horses and Americans. Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, 1939. A history of horses in America from the arrival of the Arab Plains horses sometime around 1600, through the colonial period, taking in the Revolutionary War, Western migration and Cowboys, the Pony Express, the Civil War, the U.S. Cavalry, thoroughbred racing, and so on through the early 1930s.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Chapman, Arthur. The Pony Express: The Record of a Romantic Adventure in Business. G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, New York, 1932.

- ↑ The History of St. Joseph Museum

- ↑ Financial Problems at xhomestation.com

- ↑ Scotts United States Stamp Catalogue.

- ↑ "Pony Express Sesquicentennial Banquet", St. Joseph, Missouri Travel and Tourism, accessed 9 February 2010

- ↑ American National Biography

- ↑ Wells Fargo Reaquires Name Rights from Borg-Warner ELLS May 4, 1999 Press Release

- ↑ U.S. Postal Service Expands Licensing Program News Release #06-043 June 20, 2006

- ↑ Ponyexpress.ru, Pony Express Russia (Freight Link)

- ↑ "Pony Express National Historic Trail: History and Culture", National Park Service, accessed 4 May 2009

- ↑ [Warren, Louis S. (2005) Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show.Knopf; 1St Edition edition,6 ISBN 978-0375412165]

- ↑ [Cody, William F. The Life of Honorable William F. Cody. Accessed: http://books.google.com/books?id=VpBpTb5JmKQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=buffalo+bill+cody+and+the+pony+express&source=gbs_similarbooks_s&cad=1#v=onepage&q=buffalo%20bill%20cody%20and%20the%20pony%20express&f=false]

- ↑ [Cody, William F. The Life and Adventures of “Buffalo Bill.” Accessed: http://books.google.com/books?id=rbws9JBBr9AC&printsec=frontcover&dq=buffalo+bill+cody+and+the+pony+express&source=gbs_similarbooks_s&cad=1#v=onepage&q=buffalo%20bill%20cody%20and%20the%20pony%20express&f=false]

- ↑ [Warren, Louis S. (2005) Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show.Knopf; 1St Edition edition, 6 ISBN 978-0375412165]

- ↑ [Warren, Louis S. (2005) Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show.Knopf; 1St Edition edition, 4-6 ISBN 978-0375412165]

- ↑ "The Pony Express" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Frontier Pony Express" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Pony Post" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Plainsman and the Lady" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Pony Express" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Last of the Pony Riders" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "The Pony Express Rider" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "The Range Rider" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Pony Express" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ "Bonanza" Internet Movie Database.

- ↑ Amerikids.com

External links

- Pony Express on Oregon Trail, Wyoming Tales and Trails

- George A. Root and Russell K. Hickman, "Part IV-The Platte Route-Concluded. The Pony Express and Pacific Telegraph", Kansas Historical Quarterly, February, 1946 (Vol. 14 No. 1), pp. 36–92.

- History Buff Primary Source

- Pony Express History, St. Joseph Museum Inc.

- Hollenberg Pony Express Station

- Pony Express home station

- "The Story Of The Pony Express", National Postal Museum

- The Pony Express for Kids, Pocantico Hills

- List of Pony Express resources for further reading

- James Nash 1838-1926 Pony express rider

Sources

- Century Magazine, volume xxxiv (New York, 1898)

|

||||||||||